On April 1, 1994, Paul Butcher, then the director of Colorado Springs parks department, received a chilling phone call from a frantic staff member. She told him that Balanced Rock—a 290-million-year-old red sandstone boulder naturally perched on a sloped ledge in Garden of the Gods Park—had fallen. Butcher panicked, his thoughts roiling with how disappointed and outraged both locals and visitors would be with the loss of the beloved, iconic landmark. He imagined the 700-ton boulder rolling downhill, with nothing to stop its tumble onto the nearby U.S. Highway 24, like a monstrously dense tumbleweed. Then he remembered the calendar, and realized it was a prank. “I never laughed,” Butcher, who is now retired, told Out There Colorado. “It’s not a great joke.”

In a way, the mere existence of Balanced Rock also seems like a prank, either geological or cosmic. The enormous boulder looks like it had been photoshopped onto the landscape, or photographed mid-roll, or carefully placed by aliens. But it’s no hoax and there’s no sorcery to it. Rather it is a prime example of a whole category of geologic formations called “precariously balanced rocks”—PBRs, for short. They’re exactly what you might expect. “It’s a rock balanced on top of another rock,” says Mark Stirling, who studies PBRs at the University of Otago in New Zealand. And if you think Colorado Springs’ landmark ought to have a more imaginative name, see also: Balanced Rock in Grand Junction, Balanced Rock in Rocky Mountain National Park, and Balanced Rock at the Rampart Range. And that’s just Colorado.

PBRs are more than just unusual geologic features—they’re a source of valuable scientific insight. They’re what are called "reverse seismometers" because their mere existence makes it possible to measure earthquakes that didn’t happen. If they’re still balanced, then the earth hasn’t moved enough to knock them over, at least in the last few thousand years, according to geologists David E. Haddad and J. Ramón Arrowsmith in their seminal 2011 report Geologic and Geomorphic Characterization of Precariously Balanced Rocks. So scientists study them to understand a region’s seismic history and, subsequently, predict what might come in the future. “They’re nature’s hilarious accidents,” says Amir Allam, a geologist at the University of Utah.

PBRs are a subset of a larger category called “fragile geologic features,” Stirling says. This includes any kind of rock that doesn’t meet the precise standard of a detached boulder balancing on another boulder, such as hoodoos (a mushrooming rock attached to a tall spire pedestal) and glacial erratics (boulders transported by ancient glaciers to new resting places), which are also considered PBRs when they land on another, curved rock—or a few of them, like in the case of Balanced Rock in New York's Hudson Valley. Fragile geologic features also include other landforms, such as the Punta Ventana arch in Puerto Rico that recently collapsed as a result of a series of earthquakes. Though they don’t fit neatly into PBR researchers’ equations, they can be used in the same way to assess past and future earthquakes, Stirling says.

PBRs often start their journeys deep underground. Large chunks of rock develop spidery fractures, expanded by percolating water, until they become multiple smaller chunks, Allam says. As erosion lowers the ground level, over many thousands of years, the rocks come to the surface, often stacked atop each other. “You need the right kind of climate conditions to create PBRs, and you need the right climate to make them last,” he says. “The American West is the perfect storm for this.”

The whole PBR-science idea started in the 1990s with James Brune, a geologist at the California Institute of Technology. “Brune was an old school genius,” Allam says. “He wore suspenders to all his presentations and wrote all his notes by hand.” Brune was assessing earthquake risk in Yucca Mountain, Nevada, to evaluate its future as a possible nuclear-waste storage site, when he noticed a handful of boulders balanced—rather precariously—on other stones, according to American Scientist. The boulders were all coated with desert varnish—a dark sheathe of clay, manganese, and iron oxides—indicating they had been exposed for millions of years. Brune realized the rocks offered a kind of record of the area’s seismic history, or lack thereof. So, by running PBRs through computer models that replicate earthquakes, Brune figured he could determine what level and type of shaking it would take to topple a particular rock, and then therefore rule that shaking out of its recent history.

When Brune first introduced this idea, it ruffled more than a few feathers. “Twenty-five years ago, the whole topic of PBRs was a fringe area of seismology,” Stirling says. “We were too edgy, too out of the mainstream.” Back then, he says, seismologists studied earthquakes, paleoseismologists studied prehistoric earthquakes, and engineering seismologists studied ground motion. Brune’s approach to PBRs straddled all these fields, and that kind of triple-dipping in science often leads to skepticism, Stirling says. Other early PBR enthusiasts also struggled to get funding and resources for their work. But a good idea is a good idea and they persisted, Stirling says, with Brune leading the charge. By the early 2010s, PBR science had respect within the field and funding from sources such as PG&E and other energy companies, who wanted to understand the earthquake risk for their plants.

Allam studies Utah’s seismic history, and colleagues even call him "the PBR guy." His chaotic website includes a tab for them—“PBR!”—and a quote from Japanese writer Haruki Murakami that carries extra meaning for seismologists: “My biggest fault is that the faults I was born with grow bigger each year.” Allam is particularly enamored with shaking boulders enough to knock them over—only not in real life. “It’s also because they’re really cool,” he admits.

Allam has made it his mission to map every PBR—and the forces required to topple them—in Utah. He’s compiled at least 40 so far, but the trickiest thing about studying PBRs remains finding them in the first place. Allam has a whole team of undergrads who are, rather understandably, also pretty into PBRs. “I tell them to go on Google Earth, look for rocky outcrops, and then go drive out and check it out,” he says. He also goes hiking with his students, to show them PBRs he’s already identified and rely on their fresh eyes to spot more.

Once he finds a new PBR, Allam covers it with strips of tape to prepare it for photogrammetry, in which he merges photographs of the rock to construct a 3-D digital counterpart. To assess how long the rock has been precarious, Allam measures the concentrations of cosmogenic radionuclides on the underside of the rock, which offer a history of how long a rock has been exposed. The PBRs he studies tend to be approximately 30,000 years old. “Big earthquakes happen every 150 to 1,000 years, so 30,000 years is a statistically reliable data point,” he says.

Once Allam has the model, he shakes it in a computerized earthquake simulation. He starts off small, with a peak horizontal ground acceleration of 0.2 g (that is, g-forces, or the acceleration due to gravity). If that doesn’t do it, he goes to 0.25 g, and then maybe a little bit more until it comes tumbling down. No one wants to be in the way of a real falling rock, but he’s not after a rock’s threat level. “PBRs rarely fall and hurt people,” Allam says, because most are so remote. “The earthquake itself is much more dangerous.”

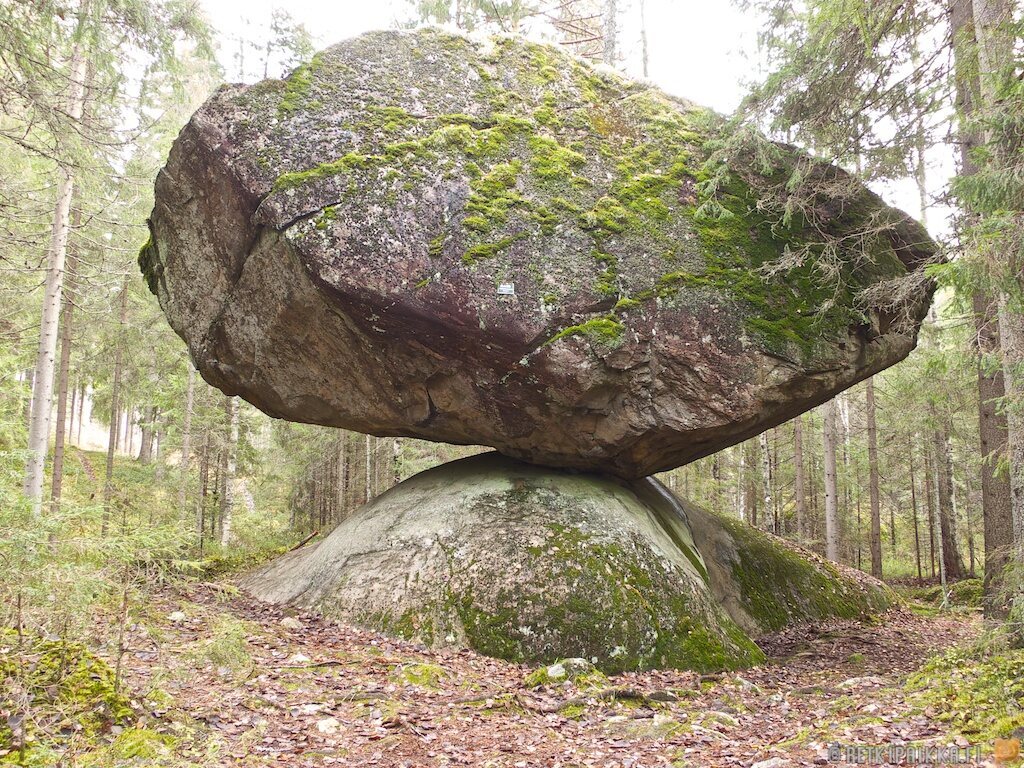

The geology of Utah makes it a great place for PBRs, but they can be found throughout the world. In Lacrouzette, France, an oak and chestnut forest cloaks a large rock that bears a famously uncanny resemblance to a goose. Mount Desert, Maine, has Bubble Rock; Mahabalipuram, India, has Krishna’s Butter Ball; and Ruokolahti, Finland, has Kummakivi. In Myanmar’s Thaton District, Kyaiktiyo, a 25-foot-tall boulder perched on the edge of a cliff wears a small pagoda like a hat. (Rocky towers along the Hudson River between New Jersey and New York are actually manmade, by artist Uliks Gryka.)

Allam’s shaking has to take place inside a lab because there is one cardinal rule of researching—or even just visiting—PBRs: Do not knock them over. All PBRs will eventually fall down, their bases worn down by erosion, their weight distribution changed by time, and the occasional earthquake, large or small. The chance of this happening to any particular PBR in a human lifetime is almost zilch, Allam says, but there is one other way that PBRs can come down.

Take 2012, when a scandal rocked the Utah Boy Scouts. Glenn Taylor, a scout leader, was filmed pushing over a hoodoo (what locals call a goblin) in Goblin Valley State Park, by a friend, David Hall. In the video, Taylor wedged himself against the boulder and heaved his weight into it. Nothing happened at first, but then the rock thudded to the ground, and Taylor high-fived his large adult son.

“It was an appalling act of vandalism,” Stirling says. Taylor and Hall were sentenced to a year of probation, after pleading guilty to criminal mischief, according to the Salt Lake Tribune.

This specter does loom over some PBRs. All it takes is a moment. “Some of the huge ones could be easily dislodged with a couple of guys and a crowbar,” Allam says. “Something the size of a watermelon, well, you could push over yourself.” Once, during one of his PBR surveys, Allam spoke with a shepherding family who say knocking over precarious rocks is a family tradition that runs back generations. “They said, ‘Our favorite thing is to roll boulders down a mountain,” he says. “Which makes sense, if you’re bored and surrounded by nothing but sheep.”

Felled PBRs—dropped by causes natural or unnatural, can be almost indistinguishable from ordinary boulders, unless you know what you’re looking for. If you see some smaller boulders scattered around an area with still-balanced PBRs, there’s a good chance you’re looking at their former neighbors, perhaps grounded by human hands. In the future, Stirling says, he hopes that fragile rock formations will be treated with the same reverence as archaeological sites.

“Once it’s toppled,” Allam says, “there’s no getting back to the past.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

This week’s post is the first in a four part series looking at what I’m going to term the Fremen Mirage (a play on Le Mirage Spartiate, which we’ve already discussed in some detail), a term I’m creating to encompass a set of related pop-history theories which are flourish, evergreen despite not, perhaps, holding up so well under close examination.

Also, Dune pictures will be from Frank Herbert’s Dune (2000) and Children of Dune (2003), because they are the best Dune. David Lynch fans, fight me.

Now, I know this will disappoint, but this is not a four-part look at Fremen culture (although, now that I say that, a deep dive into the real world analogues of the Fremen would be interesting…), though by the end of this series, you will have a good sense of how probable I find it that a low-density de-industrialized population of knife-wielding warriors would overrun a vast, dense industrialized interstellar civilization. Instead, I’m choosing the Fremen – and really the Dune series more generally – to stand in for a particular set of oft-repeated historical ideas and assumptions. It is not one idea, so much as a package set of ideas – often expressed so vaguely as to be beyond historical interrogation. So let’s begin by outlining it: what do I mean by the Fremen Mirage? I think the core tenants run thusly:

- First: That people from less settled or ‘civilized’ societies – what we would have once called ‘barbarians,’ but will, for the sake of simplicity and clarity generally call here the Fremen after the example of the trope found in Dune – are made inherently ‘tougher’ (or more morally ‘pure’ – we’ll come back to this in the third post) by those hard conditions.

- Second: Consequently, people from these less settled societies are better fighters and more militarily capable than their settled or wealthier neighboring societies.

- Third: That, consequently the poorer, harder people will inevitably overrun and subjugate the richer, more prosperous communities around them.

- Fourth: That the consequence of the previous three things is that history supposedly could be understood as an inevitable cycle, where peoples in harder, poorer places conquer their richer neighbors, become rich and ‘decadent’ themselves, lose their fighting capacity and are conquered in their turn. Or, as the common meme puts it:

- “Hard times create strong men. Strong men create good times. Good times create weak men. And weak men create hard times” (The quote is originally from G. Michael Hopf, a novelist and, perhaps conspicuously, not a historian; one also wonders what the women are doing during all of this, but I have to admit, were I they, I would be glad to be left out too).

The second and fourth are from a series of five paintings by Thomas Cole called The Course of Empire, which is itself essentially this meme, just in the 1830s. That timing, we will find, is no accident – the modern version of this idea has deep roots in Romanticism (c. 1800-1850), a reaction against the reason of the Enlightenment – which makes it more than a touch ironic that this brain-dead meme is so frequently presented as clear logic.

This complex of ideas is what I phrase as the Fremen Mirage, and as you might imagine from that word ‘mirage,’ there are real, gaping problems in this vision of history. I’ve picked the Fremen to stand in for this idea in part because – being a fictional people – they are unconstrained by the real world messiness of actual societies. Instead, Frank Herbert quite clearly intends the Fremen to be a sort of purified form of this trope, the hardest people from the hardest conditions; they’re even presented as being more extreme than another example of this same trope, the imperial Sardaukar, who also indulge in the same ‘hard men from a hard place’ idea. Moreover, Herbert plays out this cyclical vision of history in the books, with the going-soft (slowly) Sardaukar being no match for the hard-ways Fremen and the latter – despite a near total lack of modern military or industrial infrastructure and what should be a crippling manpower disadvantage – spreading out and defeating all of the ‘civilized’ armies they encounter (with attendant worries that they will will become ‘soft’ and thus weak, should their planet, Arrakis, be made more habitable).

Now, the way this trope, and its contrast between ‘civilized’, ‘soft’ people and the ‘uncivilized’ ‘hard’ Fremen is deployed is often (as we’ll see) pretty crude. A people – say the Greeks – may be the hard Fremen one moment (fighting Persia) and the ‘soft’ people the next (against Rome or Macedon). But we may outline some of the ‘virtues’ of the ‘hard men’ sort of Fremen are supposed to have generally. They are supposed to be self-sufficient and unspecialized (often meaning that all men in the society are warriors) whereas other societies are specialized and overly complex (often to mean large parts of it are demilitarized). Fremen are supposed to be unlearned compared to their literate and intellectually decadent foes. Fremen society is supposed to be poor in both resources and infrastructure, compared to their rich and prosperous opponents.

The opposite of Fremenism is almost invariably termed ‘decadence.’ This is the reserve side of this reductive view of history: not only do hard conditions make for superior people, but that ‘soft’ conditions, associated with complex societies, wealth and book-reading weenies (read: literacy) make for morally inferior people who are consequently worse at fighting. Because we all know that moral purity makes you better at fighting, right? (My non-existent editor would like me to make clear that I am being sarcastic here, and it is extraordinarily obvious that moral virtue does not always lead to battlefield success.)

That necessarily means that what makes a Fremen is relative – they are less complex, less specialized, less wealthy, less built up, less densely populated, less literate than their contemporary neighbors. After all, modern insurgent mountain fighters are frequently given the Fremen Mirage treatment, but compared to, say, the Romans (who are clearly un-Fremen, except – as we’ll see – when they’re not…) they possess a level of technology and exist in a degree of social complexity the Romans could hardly imagine.

The relativity of ‘Fremeness’ is actually one reason why I’m using the term Fremen in place of tradition or more common terms you’ll see: ‘uncivilized people’ ‘barbarians’ or ‘savages.’ Of course, it lets me neatly dash around the offensive components of those terms, but more to the point, it creates a term to describe the myth without creating a term that might purport to describe the reality. Which is to say I can say that a society is perceived as being Fremen, without actually tagging them with ‘barbarian’ or ‘savage,’ because those terms have all of the intellectual usefulness of a raincoat in the desert. It is rapidly going to become apparent that the popular idea of who does and do not count as Fremen – or its inverse, ‘decadent’ – is such an absurdly moving target as to be practically meaningless (there are a few constants, but only a few), with some societies whip-lashing between the two so fast that it makes me dizzy seeing it.

What I hope we can understand here is that when I start grouping certain societies under the term ‘Fremen,’ I am more talking about the modern perception of them, then anything to do with the reality. As will become clear, some of the classic ‘Fremen’ societies are, in fact, not only agrarian and settled, but in some cases even urbanized – which is to say, ‘civilized’ in the narrowest sense (from the Latin root) of ‘living in cities.’

Let me repeat that one more time, so that everyone hears it, by labeling a culture here as ‘Fremen’ I am not saying they are barbaric or uncivilized, but merely noting a fact about the modern perception of that culture and how it fits into this view of history.

He’s Blue, da-bo-de-da-bo-di…

Anyway, over the next four weeks, we’re going to take a critical eye to this theory of history and look at its problems and origins. This week (for the rest of this post) we’re going to take a long view and look at how the dynamic between richer agrarian societies and poorer, non-agrarian societies played out in pre-history and very early history. Next week, we’re going to take a single, pre-modern case study and examine it in detail. Naturally, because this is me, the case study will be (trumpets blaring) Rome, which fought a lot of poorer, less settled peoples and is frequently used as the example of wealthy, ‘civilized’ and ‘decadent’ military failure. I’ve opted to pick these two sets of examples to start out because these periods – classical antiquity and pre-history – ought to be the periods where our Fremen perform the best, as the technological and industrial gap between them and their richer ‘civilized’ opponents is the smallest – in some cases, practically non-existent.

In week three, we’ll look at the origins and intellectual history of this idea: where did it come from? Was it ever really about the ‘barbarians’ at all? And why did this set of ideas suddenly spring back into common usage? And then finally, in week four, we’re going to look at some of the apparent exceptions: horse-nomads, along with modern insurgents and guerrillas – these are some of the most effective historical non-state actors, so if anyone should live up to the Fremen’s billing, it has to be these guys. That also means we can dip our toes into the state of affairs post-gunpowder and even after the industrial revolution, to see if those massive changes to warfare change the balance at all.

Now, I feel the need to note at the outset that structuring the discussion this way means accepting, for the sake of argument, some of the underlying assumptions built into the Fremen Mirage: namely that the chief value of a society is found in how effectively it produces and externalizes violence…which is to say that it assumes a society’s chief purpose and thus the primary metric of judgment is how effective that society is at war. The Fremen Mirage leaves no place for assessing eloquent literature, beautiful artwork, cunning architecture, clever scientific advances, higher quality of life, or any of a host of other contributions to the richness of the human experience. For the sake of argument, I am accepting, from the get go, that this violence-oriented vision of what is to be valued in a society is valid; it will be quite obvious for those who have read my series on Sparta that I do not, in fact, think this is so, and that quite clearly a society which does nothing but fight well is not a goo society. But, so that we don’t get endlessly hung up on these priors, I am going to grant that, for the purpose of this series, we are only assessing these societies by their military capacity.

Let us fight the Fremen on ground of their own choosing. I am, for reasons that will soon become quite obvious, still fairly confident that our sophistication will prevail.

War at the Dawn of Agriculture (c. 9,000 – 5,000 B.C.)

We start our examination of the question very literally at the beginning, by asking what advantages or disadvantages were posed by the creation or adoption of ‘civilization’ – by which we mean, at this very early point, agriculture and its attendant developments of writing, urbanism, and greater social complexity and stratification. I am going to talk in generalities, but if you want specifics (and a sense of where my information comes from), and a sense of the sort of evidence (there is a lot of it, but much of it remains quite contested), I might suggest A. Gat, War in Human Civilization (2006) 146-189 and L. Keeley, War Before Civilization (1996) as starting points. The second chapter of J. Guilaine and J. Zammit, The Origins of War (2001), also discusses these questions and presents quite a bit of the core evidence. For a reasonably brisk overall summary of the question, check out Lee, Waging War (2016), 30-35.

We should begin by noting that this innovation seems to have developed not in just one place, but actually in several places at different times: in Mesopotamia, India, China, Mesoamerica, the Andes of South America, in the Sahel region of Africa, among a few others. In each case, farming – and the social structures that supported it – spread out from the initial zone of innovation to a much larger area. This process takes place well before recorded history in all cases, which means that we’re forced to use archaeology and anthropology to observe the broad outlines of it, rather than being able to interrogate it directly and historically. Nevertheless, the creation of agriculture marks the beginning of this sort of divide between what we might term our ‘Fremen’ (peoples that continued to live as hunter-gatherers) and the new agriculturalists. After all, the emergence of more complex societies necessarily meant that the people who were not in those societies were, by comparison, less complex.

Now I want to be clear that this distinction is not as sharp as it is sometimes presented. First, many hunter gatherers were not fully nomadic – most were either semi-nomadic (moving somewhat predictably within an established ‘territory’) or had even become sedentary in order to exploit a particularly resource rich zone (it is this latter group who are likely to be your earliest farmers). Moreover – and this will be a trend that will continue throughout this series – while agriculture and sedentism enabled the first real accumulations of significant wealth in human societies, it does not follow that the average agriculturalist was immediately better off than the average hunter-gatherer; indeed, there is some evidence to indicate the reverse, that the diet of the average peasant was somewhat worse than that of the average hunter-gatherer (something we’ll return to).

Nevertheless, this gives us our first case to study: the expansion of farming. Our main question is how farming spread. Under the assumptions of our Fremen Mirage, we ought to expect farming societies to be frequently overtaken and subjugated by their non-farming neighbors, who still possess all of the skills and supposed ‘toughness’ that comes from the life of a hunter-gatherer. If farming does expand under such conditions, it ought to expand by adoption – neighboring hunter-gatherers ‘going soft’ by adopting farming (since the Fremen ought to be able to outfight the early farming societies, with the latter’s greater degree of wealth and social stratification making them weaker and more ‘decadent’).

Of course, this is not what we see. First, we see that farming begins not in the most impoverished zones, but in areas that were already resource rich and thus supporting a high density of people (and thus, we may assume, higher degrees of social complexity). That is to say, farming is developed by people we might typically as the least Fremen of our pre-agricultural hunter-gatherers. That should clue us in to a problem because – and I present this as a general rule – no one chooses to live in a resource poor zone if other options are available. Which is to say, if these people control the resource rich zones, it is because they have rebuffed all efforts by their neighbors to take those zones from them. And we may be virtually certain such efforts were made (I don’t want to get into the origins-of-war debate here, but suffice to say I am of the opinion that war is a human constant, probably since before the emergence of anatomically modern humans).

Moreover, the evidence points to what we see next: it is not usually that farming spreads, but that farmers spread. In the broad sweep of things, this comes as little surprise: group-size and social complexity had been humankind’s ‘killer app’ long before farming. There is substantial evidence that larger group-size (facilitated by greater intelligence) is the thing which allowed anatomically modern humans to outcompete Neanderthal and push them into areas of progressively more marginal resources. Neanderthal was, ironically, more Fremen than the Fremen – stronger and tougher than anatomically modern humans, but it didn’t help; the numbers advantage outweighed advantages in strength or robustness.

Now, the evidence suggests that, for the most part, early farmers are doing the same thing: using their higher population density – and the attendant military advantages that brings – to displace the lower-density non-farmers. It does seem that some hunter-gatherers held on by adopting agriculture themselves, enabling sufficient population density to resist the invading farmers. But these were not the hunter-gatherers in the toughest, most marginal, ‘hardest’ places, but rather the hunter-gatherers in the softest, easier plaes which could support the higher population densities necessary to hold off the farmers. Thus, for instance, the farmers – coming out of the Near East – appear to have overrun much of Europe, but along the resource-rich European shore-line, in Spain and the Baltics, the more densely population and prosperous Mesolithic societies of complex-hunter-gatherers were able to hold off the farmers long enough to adopt farming themselves.

Elsewhere, the evidence suggests that the hunter-gatherer population was pushed on to more marginal lands (arid areas, hills and mountains, for instance). Again, it seems fairly safe to assume this was violent – I am fairly sure, if you decided to push me off of my good, rich land full of tasty wildlife, I would at least try to stop you and I would probably get quite violent about it.

Now, it is also that this point that we get the emergence of people living another kind of lifestyle: pastoralists. That is, instead of being hunter-gatherers or being farmers, these are people who mostly raise animals, typically on land that is too marginal for proper farming (usually because it is just a touch too arid or mountainous). We’ll talk about them more in Part II and Part IV. For now, I want to follow our farmers just a bit more.

The Beginning of States (4,000 – 1,500 B.C.)

So we’ve seen in the previous section that, for the most part, what we see is that our farmers, with a more prosperous and complex society, spread largely by out-competing (and probably violently expelling) groups of hunter-gatherers. Now we’re going to move forward a few millennia and layer over that another level of social complexity: the state. As before, if the Fremen thesis holds, we ought to expect that state societies – larger, more complex, with greater wealth, specialization and social stratification – should be militarily weaker than non-state peoples and thus ought to struggle to spread.

(Bibliography sidenote: if you want to read more about state formation, I suggest Gat (2006), 231-322. There is an able summary of the basics in Lee (2016), 35-45.)

But before we get into that, we need to talk about what we mean by the state. The state is a system of social organization that is so prevalent in today’s world that all too often we take it for granted that it is the only form of social organization, or the chief one, when in fact it has been around for only a tiny minority of our species’ tenure on this planet. Now the modern, political-science definition of a state today tends to run something like this (this is, for the curious, Max Weber’s definition): a state is a political entity (a polity) which exercises a monopoly on the legitimate use of force within a given territory. Another way of defining the phenomenon – and one more useful in the very early stages of state-formation – is to define a state as (to use Wayne Lee’s formulation of the common definition from Waging War, 36), “a society with marked social stratification, with a centralized and internally specialized government capable of extending bureaucratic control out into a settlement hierarchy” consisting of multiple (at least usually three; center, regional centers and subordinate communities below them) tiers.

The state, as an idea, didn’t emerge in just one place, but – like agriculture – it emerges in a number of different places (there is some debate as to exactly how many) independently at different times. We call these first states (more correctly, the first state-systems) – ones that sprung up without any connection to a preexisting state – pristine states. What is immediately striking is that the places these pristine states emerged – Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Andes, Mesoamerica, northern China, etc – are many of the same resource rich zones where agriculture had emerged. States everywhere form first in the zones of most intensive agricultural exploitation and densest population. Rather than hard, difficult country being the breeding ground for the state, it is in fact the richest, softest areas that were (for those who have been to Mesopotamia and are wondering why it doesn’t seem quite so rich and soft anymore, the word you want to look up is salinization).

Note how well these map on to the same areas (see above) that were the resource-rich, high-density zones which first produced agriculture, even though this is happening many thousands of years later in most of these regions (e.g. farming in Mesopotamia c. 9,000 B.C., states c. 4,000; farming in China c. 7,000 B.C. states in c. 2,000), when agriculture had already spread very widely.

Now when we’re talking about the emergence of the state, what we mean is a process by which one of these farming communities (by this point, we are looking at early towns) – or more correctly, the military elite of those communities, for the role-specialization enabled by farming has begun, by this point, to create a military/religious aristocracy – is subjugating neighboring farming communities. Towns subordinate the villages in their orbit, and eventually also smaller towns (these become the ‘regional centers’ in our definition above) who have subordinated the villages in their orbit.

The military competition between these communities provided the impetus, and the resources of subordinated communities provided the fuel, for the establishment of new systems of power, both military and civilian. Even as the most militarily success communities establish hierarchies over their peers, often enforcing tribute or even slavery on defeated communities, so the most successful individual military-specialists (and their followers) are lifted up above the community, creating a military aristocracy, arrayed around the family of that successful leader – the origin of kingship. And so early state formation, essentially everywhere it occurs takes the form of the emergence of not just monarchy, but a specific, recognizable form of monarchy: kingship.

With that went the formalization of certain kinds of government control – gifts to the proto-king are formalized as taxes and tribute (to be funneled into military expenses, primarily) tribal militias are brought more fully under the control of the proto-king to become compulsory levies, led by the king’s retainers (who increasingly were a often-hereditary military/civil-administrative elite). The most successful early states become small empires, drawing tribute from the periphery to supply and fund the military activity of the hegemonic community at the center and its military leader (by this point, a king): a ‘military-tributary complex.’

So nice of the Egyptians to create such a striking pictorial documentation of the violent unification of Egypt.

In short, the process of state formation is one by which – driven by the demands of intense military competition between agricultural communities – the level of social stratification, specialization and complexity increase towards the development of complex hierarchies of specialists (most of whom are specialist farmers) and the creation of institutional forms of power, as well as enabling the first spectacular accumulations of wealth in the ruling class of these new societies. In short, the state is the least Fremen thing possible, and state formation is a move away from what we might term Fremenism – where the Fremen are egalitarian, the state is stratified; where the Fremen social structure is simple, the state is increasingly complex; where the Fremen are all hard, ‘badass’ generalist warriors, the state is specialized and consists of large numbers of demilitarized specialist-farmers; where the Fremen are poor, the rulers of these new states are the first mega-wealthy. They were the least Fremen people who existed at the time. It is important to keep this in mind; it is easy to lose perspective in terms of what a ‘rich’ or ‘poor’ society look like at any given moment in time, although state formation tends to be when societies start displaying their wealth in very obvious ways, like by assembling masses of prestige goods (gold, jewels, spices, expensive fabrics, etc) and building megalithic structures like massive temples and palaces.

There’s a lot more to this process – one day we’ll talk more about state formation on its own – but I wanted to lay out the basic outlines because I want to show how central military power is to this process. While the state produces all of these very un-Fremen things: social complexity, increased specialization, bureaucracy (which in turn leads to literacy and from there to very un-Fremen literature) and the accumulation of large amounts of wealth, it does so in the pursuit of military power. And it worked: the state was and remains the single best organizational principle for the creation and direction of violence ever derived. With only a handful of exceptions (which we’ll discuss in the final part of this series), the potential violence the state can bring to bear wildly outstrips the capacity of other forms of social organization.

All of which leads into how the state spread: whereas farming spread through the spread of farmers, the state spreads as an idea, jumping across culture and linguistic barriers, eventually reaching the point we are at now, where we can imagine the populated parts of the world as broken entirely into a network of states (although in practice, our maps conceal quite a lot of non-state peoples and areas beneath the clean, pretty lines).

This collection of institutions and social structures, once developed, proved so much more capable of mobilizing the resources of an agrarian society to produce military force than the tribal systems of organization that proceeded it, that tribal societies that found themselves in the path of expanding states tended either to be subjugated (and thus learn state institutions ‘from below’ as it were) or else were compelled to develop state institutions themselves in order to compete (a process we’ll look at in more detail in Gaul and Germany next week, but also note 1 Samuel 8-13, where the Israelites demand a king ‘like the other nations have’ in order to compete militarily).

In short, the rise of the state as a system of human organization seems to be one in which the richest, most densely populated and socially complex farmers, in direct competition with each other, developed progressively more complex social forms, with greater amounts of specialization and hierarchy, which was so effective in increasing these societies’ ability to project military power that their neighbors were forced to adopt the innovation, one way or another (and then their neighbors, and so on, but see the caveat below).

Where States Fear to Tread

Now, a you might imagine, there are some exceptions to the expansion of both farming and states and these are worth noting.

Farming, of course, is heavily constrained by geography: the land has to be arable (not too rocky, not too acidic, not sand), with sufficient water to support crops and (generally) not mountainous. These are not iron-clad rules, some non-arable land can be loosened and tilled into arability (but at a cost), water may be brought to the land by irrigation and in some cases even the sides of mountains may be farmed through terrace farming. But these are all difficult and labor-intensive ways of farming the unfarmable and suffer rapidly diminishing returns. Significant land areas are simply not very suitable for farming (it is worth noting that the qualities which make for good farmland are also generally what a hunter-gatherer or a pastoralist might want in an area of land, so this land is going to be fiercely competed over).

But, of course, a lot of earth’s available surface is these kinds of relatively unfarmable places, areas of deserts, mountains, grassland with too little water for farming, and so on. These places were not empty. Chronologically quite closely to the advent of farming, another form of subsistence evolved in these unfarmable places: pastoralism, which is to say animal-husbandry. Herds of animals may be subsisted off of grasses in land with greatly insufficient fertility to support farming.

I don’t want to get into all of the possible permutations of pastoralism, from mostly stationary ranching to transhumance to true nomadism – that’s for another time. But I do want to note the existence of these unfarmable places, because they are places that the state struggles to go, and in some cases can never truly go into. The state, as an organizational system, is fundamentally based on farming communities: densely populated, sedentary and highly specialized. But pastoralist societies are often thinly populated, transitory and largely unspecialized. Whereas an expanding state could simply convert tribal farmers into new state subjects, relying on the (borrowing the idea from Landers, The Field and the Forge (2005) demographic space created by those farmers (the available agricultural surplus, community centers like towns and villages to serve as administrative centers, transportation infrastructure, and sedentary farmers) to do so, pastoralists are a difficult fit with the state. They often don’t stay neatly in one place for the purpose of taxation or extraction, there is no easy administrative center to organize them, and – knowing that their rough terrain gives them a degree of insulation from state control – they tend to be truculent.

Here we seem to finally have some real Fremen – a low-population density community that is able to resist the encroachment of the highly complex and sophisticated state. And to a degree there is something to this, but we should not that in most cases, it is not the people or their military prowess that keeps the state away, but the land itself. And the level of protection the land provides varies.

In many parts of the world, these pastoralists found themselves effectively ‘enclosed’ by a state – surrounded on all sides – and thus tamed by it. This was the experience, for instance, of the hill peoples of Italy, who often fiercely resisted the expansion of the Roman Republic, but were eventually unable to stop it. In areas of the world where the pastoral zone was small, where it afforded relatively little protection against the larger armies of complex states, this is largely what happened.

But of course there are some areas – the borders of the Sahara, the Arabian Desert and most crucially the Eurasian Steppe, where this unfarmable zone stretches on and on, creating a vast zone that farmers – and consequently the state – could not penetrate. As we’ll see a bit later in this series, this was not always because the people who lived in those zones had superiority in a direct fight (though they sometimes did), but that when they were militarily weaker (which was usually as it turns out), the state could not press its advantage and consolidate control of them because the agrarian armies of the state could not penetrate this area – what K. Chase calls the ‘arid zone’ (in contrast to the vast sweep of agricultural land running east-west from China through India to Mesopotamia into the Mediterranean, which he calls the oikumene after the Greek word meaning ‘the inhabited world.’).

We’ll talk more about the most successful residents of the arid zone a bit later in this series. But what I want to note for now is that, as the name ‘arid zone’ implies, this was, by and large, a resource poor part of the world. It was the marginal land: if you could be anywhere else, you would be. And so while, with the rise of pastoralism, we have the emergence of our proto-typical Fremen, they are hardly the world-conquerors we were told to expect. Instead, they appear as the losers of the expansion of farming and the state, peoples shoved out into the worst land, forced to eke a living out there and protected, not by their badass military skills, but by the sheer uninhabitability of where they live. And remember: (almost) no one chooses to live in a resource-poor zone if they have other options.

Now, before we conclude for the week, I want to note some necessary caveats. This march of agriculture and the state I’ve laid out doesn’t mean that farmers and states always win, merely that – in areas where agriculture is possible – they usually won. It certainly is the case – as we’ll see next week – that sometimes settled states are overthrown by, for instance, migrating pastoralists (e.g. the Amorites moving into Mesopotamia c. 2000 B.C.) or steppe nomads. As we’ll see, because these peoples often live in areas where – because they are unsuitable for agriculture – the state cannot generally follow them, they essentially have unlimited ‘at bats,’ able to retreat and regroup in their own homelands to try again later.

Nevertheless, the idea at the core of the Fremen Mirage is that the Fremen are militarily stronger in a general sense. If I may lean on a sports analogy, we would not call a team ‘better’ if they lost 98 games but happened to win the last 2. The question is both the ratio of victories to defeats, and the impact of those results. And that’s why the march of the state and of farming is so instructive: we can see the same process repeat itself, in a wide variety of areas, over very long periods of time, with what must have been many hundreds if not thousands of small wars. And it is quite clear from that evidence, that at the dawn of civilization, it was the least Fremen societies who tended to win the most.

Next time: we’re going to look at how one of the wealthiest, most complex and sophisticated states of its day (Rome, natch) dealt with conflict with a variety of less wealthy, frequently less complex neighbors and ask: do the ‘barbarians’ – our Fremen – always win? Do they generally win? Do they hardly ever win?

Run! The rest of this news post is a trap. If you keep reading I’ve little doubt you will wind up Slay The Spire‘s spire once more, and your evenings will congeal into glorious ascent. The latest character has escaped the beta branch, and is ready to tackle the spire proper. The Watcher is a blind monk who weaves between rampant aggression and calm repose. I like her a lot.

Patch 2.0 also throws in some new potions and relics, so it’s worth revisiting even if she isn’t your cup of tea.

Welcome to the first of a new set of a posts, which I’m calling A Trip Through the Classics. This won’t be a series so much as a new format we’ll have sometimes (like the kit reviews). For each trip through, I’m going to pull a key passage from a historical author – mostly ancient authors to start out – which sets out some novel, interesting or enduring ideas. We’ll discuss the author’s background, where known or relevant, explain the passage itself (key concepts and ideas), and then discuss its enduring relevance.

Most of all, in these trips through authors I want to extol the continuing value of reading these works and engaging with the deep thinkers of the past to develop a deeper view of our own world. Some of the authors in this series will be the traditional ‘great books’ sorts – like Thucydides here today – others will (I hope) be more obscure. While I’ve called this A Trip Through the Classics, I do not intend to limit myself either to classical antiquity or to any particular canon. We may also visit the same author more than once – I have no doubt will will come back to our subject for this week in the future.

So, without further ado, A Trip Through Thucydides.

Background

The Author: Thucydides (c. 460-400 BC) was an Athenian general, politician and historian who lived through the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) – the war between Athens and Sparta – and chronicled much of it (his history breaks off in 411, but was clearly composed after the war ended in 404; Xenophon’s Hellenica is intentionally positioned as the companion ‘second half’ of Thucydides’ work). Thucydides was – briefly and largely unsuccessfully – a commander in the war, appearing in his own work (4.104-107). He was punished for his failure to save Amphipolis with exile, which he spent traveling and recording details for his history.

Thucydides was thus a well-connected and well-to-do Greek. Like many elite Greek men, his training will have been directed towards a career in politics (his training in rhetoric is evident throughout his history) and he clearly thought about politics – especially matters of peace and war – very deeply.

The Passage: The passage here is a short part of a set of dueling speeches offered in the first book of Thucydies’ history. The essential background is this: the two greatest powers in Greece are Athens (which holds about a third of the Greek cities as subjects, having converted the Delian League – a mutual defense league against Persia – into its own private empire) and Sparta (which is allied with about a third of the Greek cities through the Peloponnesian League, its own – and older – mutual defense league, which Sparta dominates).

Corinth – a Spartan ally and one of the major Greek states (Athens and Sparta were the greatest of the Greek states, with Thebes and Corinth as weaker, but still significant, major states) – outraged at a sequence of Athenian provocations we need not get into here, has come to Sparta demanding that Sparta and the Peloponnesian League take action to stop Athens’ behavior and also to halt the steady rise of Athenian power. Sparta is considering the arguments.

Each of the speeches – which are probably not those which were given in the event, but rather later compositions by Thucydides expressing the ‘gist’ of what he thought was said – is a masterclass of rhetoric and shrewd political thinking. Keep in mind, the audience for all four speeches is the Spartan assembly, which must decide if it will go to war or not. They run thusly:

- The Corinthian Speech lays out the case against Athens, as well as Sparta’s obligations to their allies (1.68-1.71)

- The Athenian Speech – given by Athenian envoys who happened only by chance to be present – defends both Athenian contributions to collective Greek liberty and the acquisition and continued defense of the Athenian empire. The longest of the four, it is a section of this speech we’ll look at in a moment (1.73-1.78)

- The Speech of Archidamus, one of Sparta’s two heredtiary kings, which cautions the Spartans against a hasty rush to war. The second longest speaker of the four, Thucydides presents Archidamus very much as the wise course not followed by the Spartans – his predictions are largely borne out by the war (1.80-1.85)

- Finally, the Speech of Sthenelaidas, one of Sparta’s ephors, offers a short and devastating retort to the Athenians and a call for war; the Spartans vote with Sthenelaidas (though by a narrow margin) and the war begins (1.86).

The Passage

The following translation is by Richard Crawley (1910), with a few modifications by me; I went with this translation because it is out of copyright and freely available online. That said, I strongly recommend, for anyone interested in studying Thucydides, The Landmark Thucydides, ed. R. B. Stassler (1996), mostly for its excellent explanatory notes. Emphasis below is mine.

1.75: Surely, Lacedaemonians, neither by the readiness that we displayed at that crisis [the Persian Wars], nor by the wisdom of our counsels, do we merit our extreme unpopularity with the Hellenes, not at least unpopularity for our empire. [2] For, that empire we acquired by no violent means, but because you were unwilling to prosecute to its conclusion the war against the barbarian [the Persian Empire], and because the allies attached themselves to us and spontaneously asked us to assume the command. [3] And the nature of the case first compelled us to advance our empire to its present height; fear being our principal motive, though honor and interest afterwards came in. [4] And at last, when almost all hated us, when some had already revolted and had been subdued, when you had ceased to be the friends that you once were, and had become objects of suspicion and dislike, it appeared no longer safe to give up our empire; especially as all who left us would fall to you. [5] And no one can quarrel with a people for making, in matters of tremendous risk, the best provision that it can for its interest.

1.76: You, at all events, Lacedaemonians, have used your supremacy to settle the states in Peloponnese as is agreeable to you. And if at the period of which we were speaking you had persevered to the end of the matter, and had incurred hatred in your command, we are sure that you would have made yourselves just as galling to the allies, and would have been forced to choose between a strong government and danger to yourselves. [2] It follows that it was not a very wonderful action, or contrary to the common practice of mankind, if we did accept an empire that was offered to us, and refused to give it up under the pressure of three of the greatest motives, fear, honor, and interest. And it was not we who set the example, for it has always been set down that the weaker should be subject to the stronger. Besides, we believed ourselves to be worthy of our position, and so you thought us till now, when calculations of interest have made you take up the cry of justice—a consideration which no one ever yet brought forward to hinder his ambition when he had a chance of gaining anything by might. [3] And praise is due to all who, if not so superior to human nature as to refuse dominion, yet respect justice more than their position compels them to do. [4] We imagine that our moderation would be best demonstrated by the conduct of others who should be placed in our position; but even our equity has very unreasonably subjected us to condemnation instead of approval.

The Athenian Argument

Let’s start by quickly breaking down the Athenian argument in these passages into plain language. The core Athenian argument in this passage is that Athens has done nothing wrong which would thus justify punitive action by Sparta. This is a tricky argument in the context: while Athens did assume leadership of the Delian League without violence, by this point Athens is extracting tribute from a large number of Greek cities which (it is increasingly evident by this point) are held to Athens by cold force of arms. Efforts by Athens’ subjects to avoid paying tribute have been met with sharp military force. The Greeks had a sense that an independent city – a polis – ought to be free and unbothered by other powers, a sense summed up in two kinds of freedom, autonomia (lit: self-laws, in practice the right of the community to govern itself internally) and eleutheria (literally freedom – as in the state of not being a slave – but in practice meaning independence). Athens’ empire, by this point historically, has clearly run afoul of both.

In the face of that problem, the Athenians resort to a fairly bold plan – rather than a simple tu quoque (lit: “you also”), asserting that the Spartans would have done as they did (though they do that), they leap to a far grander premise: that Athens has acted as any state would have, and indeed more justly than some states might. Since Athens’ behavior isn’t exceptional – it hasn’t transgressed beyond the “common practice of mankind” (τοῦ ἀνθρωπείου τρόπου) – it cannot be worthy of exceptional response, like war. What makes this fascinating is that Thucydides has now put his Athenian diplomats in the position of positing a universal rule of foreign relations to which Athens has held, and thus to a degree turning them into a mouthpiece whereby Thucydides can present some of his own thinking on the topic.

Again, to follow the argument, the Athenians are asserting first that there is a set of rules which govern the behavior of states (fear, honor, interest) which may be observed to exist and that second no state may thus be faulted for behaving in accordance with these rules. There is thus both an ‘positive’ (or objective/fact-based; ‘what is’) observation and a normative (or value-judgment; ‘what we ought to do’) based conclusion; the former serves as the foundation for the latter. It is important not to merge those two steps; the core of this argument is about what is, which is only then used to explain what ought to be.

Core Idea: Fear, Honor and Interest

The Athenians claim that what influenced them in their decision making are three key motives, which appear both in the acquisition and maintenance of their empire: fear (δέος), honor (τιμή) and interest (ὠφέλεια). Consequently, these are asserted to be three of the greatest motives in foreign relations generally, which govern – and according to the Athenians, must, inescapably govern – the behavior of all states (and thus, consequently, no state may be faulted for following them). Let’s break those down, because they are sometimes, I think, misunderstood.

Greek has a few words for fear, of which phobos (φόβος; the root of our word ‘phobia’) is the most familiar to English speakers; but Thucydides here uses deos (δέος). Where phobos is an unreasoning terrified panic (the fear of the sudden onset of battle, for instance), deos is a more general word – more a dread of or a desire to avoid a thing to come in the future. It has a greater sense of reality and reason – deos can be a reasoning, well-informed fear about future events, even quite distant ones. Thucydides is thus not asserting a ‘right to panic’ but a right to look forward to future dangers and act in advance to preempt them. In this sense, the motive of fear means that states will try to – and have a right to – proactively avert negative future outcomes for themselves. In particular, fear comes first because the primary concern of all states is survival. We might sum up fear by then saying that Thucydides contends states will fight to exist.

The word here translated as interest, ophelia (ὠφέλεια) has a number of meanings, such as ‘help’ or ‘aid’ (which is why it is sometimes used as a given name, as in Hamlet), but also ‘profit, advantage, gain’ or even ‘loot’ or ‘spoils’ (as in, stuff seized in war). Ophelia is a thing you get – by any means – which renders you better off. Thus interest, in this context, means that states will pursue their own gain or profit – or that of their citizens – at the expense of other states. Naturally, the ophelia of one state must often interfere with the deos of another – my greedy eyes looking over your resources may cause you to fear me.

Finally, the most easily misunderstood of the three, honor, timē (τιμή, pronounced ‘te-may’ not like time). We tend to think of ‘preserving the national honor’ as consisting of acting ‘honorably’ which in turn means acting in accord with some rule of moral conduct. ‘She is an honorable person’ is roughly synonymous with ‘She is a good person.’ This is not what Thucydides means here. Timē is honor in the sense that it is the dignity or respect paid to a thing; it can even mean the value or price of something for sale. There is no moral component in timē – timē is about the respect paid, not about being worthy of respect.

What Thucydides is signalling here is the need to retain a certain reputation – for effectiveness, trustworthiness, ruthlessness, vengefulness – for a state, all of which gets neatly summed up by timē (and often goes by the term ‘credibility’ in modern policy debates). Consider modern nuclear deterrence theory as an extreme example – deterrence is maintained not by launching nuclear weapons, nor by being willing to to do, but by the belief of other states that you will – a point made by Bernard Brodie in The Absolute Weapon (1946), as he writes, “the prediction is more important than the fact.” Timē is how you generate that prediction – that you will be a strong ally and a dangerous enemy – by establishing a reputation, through a strong record, of being just that. In turn, that means that a great power cannot afford to be nice, because it has to maintain the kind of reputation that deters enemies and convinces friends that they will be defended. That means brutal, tit-for-tat retaliation.

I should note that this sort of reputation which is summed up here by timē was, if anything, more important in the pre-industrial world than it is now. Today, it is possible for one state to get a pretty good sense of the military power of another because the information is often readily available. But pre-modern states often struggled to have a good sense of their own manpower or resources, much less the resources of others (there are exceptions, of course, and ‘struggle’ here does not mean ‘fail’). Thus in deterring, for instance, a Germanic tribe on the Roman frontier, the Roman reputation could be far more real and valuable than, say, three Roman legions several hundred miles away. The German tribal leaders cannot see or even potentially know about those legions – but they can hear rumors of the brutal vengeance of Rome.

I think this is often missed in international-relations examinations of pre-modern diplomacy, because ideas like timē end up being treated as cultural values, rather than as utilitarian components of foreign relations. And, to be fair, the ancients themselves often group these ideas together and assign them great moral value. But if you look at the conduct of foreign relations, you can see the gloves come off – and every ancient diplomat seems to have known that an appeal to timē (or Roman fides, ‘keeping bargains’ – one of these days, we’re going to talk fides) was far stronger than an appeal to ‘justice’ or ‘mercy.’

These three motivations form a set of postulates in a proof which the Athenian envoys bring to its inevitable conclusion in the next sentence: “it has always been set down that the weaker should be subject to the stronger.” This line is often translated as “it has always been the law” which is a fair translation – the verb here (καθίστημι) has the sense of ‘appointing’ or ‘setting down’ but in this context, it really has the sense of implying a law – not in the sense of a legal issue, but a law like the law of gravity or the laws of physics, a fundamental constraint of the universe we live in. The strong will dominate because of interest, they will hold their domination out of fear and honor, and the weak will submit out of fear themselves.

It is the inescapable conclusion of the initial supposition – hard to resist – that the actions of states are driven by those three greatest motives: fear, honor and interest. Interest will cause the stronger to seek resources and control at the expense of the weaker; fear will – as in the Athenian case – cause the state with empire to cling ever more tightly to it (the traditional modern metaphor is one riding a tiger – empire is dangerous to ride, but far, far more dangerous to get off); honor will ensure that no state feels it can back down from a threat or a promise once made.

Significance

What Thucydides has the Athenian envoys lay out then is a theoretical foundation – not the only one, of course – for understanding international relations. States guided by fear, honor and interest are fundamentally amoral, as the Athenians point out – the Spartans only cry ‘justice!’ now because it is in their interest (and Thucydides implies elsewhere, because they are touched by fear of Athens); when they were unafraid and had nothing to gain, the justice of Athens’ empire concerned them little.

Like many great ideas, this is one that seems obvious in retrospect, but it is hardly so. Most discussion of international relations in the ancient world – heck, in the pre-modern world writ large – was fundamentally moral in nature, primarily concerned with right action and the concepts of justice and injustice, along with conforming to certain religiously based rules of conduct or observance. I don’t want to sound like this kind of writing – ‘mirrors for princes’ as the genre is generally known – is simplistic or stupid; such works often display moral thinking of remarkable sophistication, realism and intelligence. But what Thucydides offers is something quite different.

What we have here is the first – and one of the more eloquent – articulations of the international relations (IR) theory known as realism. Realism strips away the moral architecture we often apply to peace and war, and instead attempts to understand the actions of states by considering each state as a unitary, amoral actor pursuing its own interests in a situation where there is no other power – like a moral law or divine agency – which governs the actions of states. Consequently, states in that international system pursue power – often ruthlessly – in order to secure their own continued existence.

Thucydides’ realist views were picked up – in whole or in part – by later classical historians and from there made their way to Niccolo Machiavelli and Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes – in addition to his political treatise Leviathan, one of the founding works of realist political thinking in the modern period – also produced the first translation of Thucydides into English; the through-line from Thucydides’ realist thinking to the modern school of international relations is not hard to draw.

What I find striking is that while Thucydides presents this theory in his histories, he also seems to grapple with a number of its shortcomings. After all, the Athenian envoy’s realist appeal does not – in the event – succeed. While Archidamus – the Spartan king – also advises a realist caution, it is the ephor Sthenelaidas’ fundamentally moral appeal which wins over the Spartans. He declares – in a brief and sharp speech, “The long speech of the Athenians I do not pretend to understand. They said a good deal in praise of themselves, but nowhere denied that they are injuring our allies and the Peloponnese. And yet if they behaved well against the Persians then, but poorly towards us now, they deserve double punishment, for both having ceased to be good and for having also become bad.” Which, I feel it necessary to note, is what we might call – caution, technical term – a ‘sick burn.’ Realist analysis may be true, but it may not be persuasive.

But there’s more to it than the persuasiveness of realist appeals to naked power and interest. It is that fundamentally moral argument which drives the Spartans to act in a way that Thucydides clearly thinks is against their interest. It is quite obvious from the subsequent narrative that Thucydides sides with Archidamus – this is the wrong moment for Sparta to go to war (the right moment will come a couple of decades later). And yet Sparta unpredictably – and catastrophically – miscalculates anyway. The role of cultural and religious norms, along with interactions within states are often neglected in realist IR theory, to their detriment. Of course, one might well argue – as the Athenians do – that it was not the moral calculation, but fear and interest wish pushed the Spartans to act, but I think the presence of Sthenelaidas’ speech in the narrative speaks to Thucydides’ realization that moral arguments can sway states to act for reasons beyond pure fear, honor and interest (but cf. Thuc. 1.88.1, where he attributes the decision to fear of the growth of Athenian power).

I also want to address, briefly, the idea that this vision of Thucydides creates a ‘Thucydides Trap‘ – that a situation with a rising power and a dominant, but falling power must necessarily result in conflict. I think this view arises from an overly simplistic reading of Thucydides. If anything, the first book of Thucydides’ history stresses the number of ‘off-ramps’ not taken to avoid war as well as how the rising tensions between Athens and Sparta were not inevitable, but a consequence of a series of short-sighted decisions (often motivated more by values and moral arguments than by fear, honor and interest!). Almost nothing in Thucydides’ history is inevitable; indeed, I would argue that the contingent nature of events is, in fact, one of his most important ideas (in stark contrast to the divinely motivated fate of Herodotus or the semi-divine tyche of Polybius).

Likewise, I find the criticism of Thucydides that regards him as nothing but a heartless cynic simplifies his tale and its purpose. Unlike Machiavelli (who will no doubt make his own appearance in this space before too long), Thucydides does not part ways with systems of value entirely. His critiques of the Athenians ‘always grasping for more’ both as folly but also in some sense as a moral failing, of pig-headed Spartan shortsightedness and his keen interest in the extreme suffering brought about by the disastrous decision-making on all sides of war bespeak a thinker concerned with more than just power politics.

None of that is to discount the significance of Thucydides’ vision of international relations as expressed in this passage; realism remains one of the most dominant lines of IR thinking for a reason – because its predictive and explanatory value is quite high. States do seek to maximize their power in international systems – at the expense of their neighbors – much of the time. The rule that – as Thucydides will have the Athenians quip to the Melians later in his history – “you know as well as we do that right is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must” (Thuc. 5.89; this argument, it must be added, doesn’t carry the day here either!) has been true more often than not in history, and is sadly true more often than not today.

Not only as a annalist of single – albeit quite important – conflict, but as a strikingly sophisticated political thinker laying out a clear and clear-headed political philosophy (one that is not only influential, but seemingly dominant in modern thought!), Thucydides is well worth your time to read in full.